Introduction

Between 1842 and 1843, a small pavilion was built for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in Buckingham Palace gardens. It was an arabesque folly intended for little else than a summer retreat, offering an elevated view of the lake and grounds beyond. But within a year, that pavilion was rededicated to another, grander purpose: to serve as a test site for experiments in architecture and art, including fresco painting, which was newly revived in Germany and being considered in England as a possible medium for large paintings inside the Houses of Parliament. After its destruction by fire in 1834, this set of structures, also known as the Palace of Westminster, was being rebuilt in grand, vertical neo-gothic style (as designed by Sir Charles Barry). Questions of its interior decoration soon came to embroil royalty, politicians, artists, and critics. In 1840 a select committee was formed to determine what kind of art should be commissioned for the new building. Following much debate, the committee recommended fresco as the medium most conducive to "the advancement of the arts" in England.

As a result, by the early 1840s fresco painting in England was considered a topic of general interest and, by some, "an affair of national importance." For a time that "affair" became narrowly focused on Victoria's garden pavilion in the backyard of Buckingham Palace. Eventually, this curious building was decorated with frescos, encaustics, designs, and furnishings, the work of approximately three dozen artists and craftsmen, including some of the best-known names of mid-nineteenth century British art. The pavilion's timeline, from its construction to its demolition in 1928 reflects the challenges its design and decorations created, the aesthetic and political values it was understood to embody, and the controversies that swirled around both.

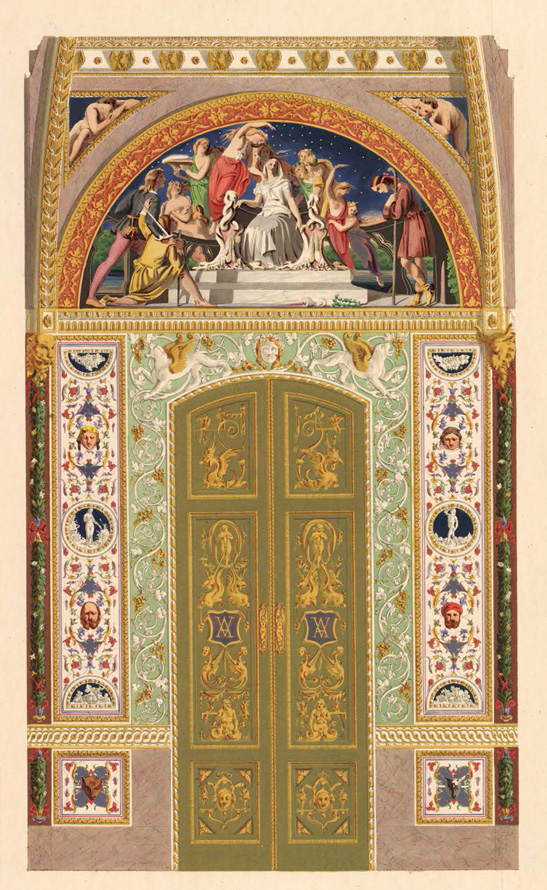

By July 15, 1842--almost immediately after Prince Albert proposed plans for the pavilion--funding for the building was approved by the Office of Works in the amount of 250 pounds, and the British architect Edward Blore, who had been responsible for the rebuilding of Buckingham Palace during the 1830s, was selected to design the pavilion. Within eighteen months it was completed, and for the next two years the pavilion served as a hub of artistic activity, despite having only three rooms and under 300 square feet of floor space. The central octagon room was decorated with frescoes of scenes from John Milton's masque Comus painted by eight well-known artists of the period: Daniel Maclise, Charles Eastlake, Clarkson Stanfield, Thomas Uwins, Charles Leslie, William Ross, Edwin Landseer, and William Etty--whose fresco was later replaced by one from William Dyce. This room was perceived to represent the heroic pastoral style, whereas two small side-rooms were decorated with frescoes inspired by the novels of Sir Walter Scott (representing the Romantic temperament) and encaustic paintings of artifacts recovered from Pompeii (representing the classical tradition). Enhancing the effects of this work were elaborate ceiling details, cornices, friezes, floor designs, and bas-relief figures rendered in materials ranging from marble to paper mache. With these three primary rooms, the pavilion was thus a small structure that nonetheless concentrated the (perhaps incongruous) varied styles and efforts of dozens of named and unnamed painters and artisans.

By February of 1844 all frescoes but Landseer's had been completed. In May of that year supervision of the work in the pavilion was turned over from Charles Eastlake to Ludwig Gruener, a German expert in fresco painting. By July of 1845 the interior design work was complete, and it included specially commissioned furnishings along with its elaborate art works. It was opened to the press for invited viewings, and a substantial number of reviews were printed in the periodical press, not all of them in agreement about the avant garde architectural, artistic, and design experiments embodied in the pavilion.

Subsequently, the pavilion served as a private retreat for the Royal family and sometimes also used to entertain small parties. (The building also contained a small kitchen.) But, as her journals show, Victoria's visits to the pavilion dropped off significantly, practically ending with Albert's death in 1861. In September of 1875 the frescoes were removed and taken to the Cross Gallery in Buckingham Palace to be preserved, but they have now disappeared. After Victoria's death in 1901, the building was barely used at all. It fell into disrepair during World War I and was razed in 1928.

Still, at the center of a visible and public conversation about the status of the arts in England, the Queen's Garden Pavilion in its heyday was a nexus of taste-making, technical experimentation, and the mythical reimagining of Victorian Britain. It is worth being remembered and digitally renovated not because it tells a coherent story, but because it concentrates so many historical narratives, none necessarily dominant but now once again available for new interpretation.

Next --> The Pavilion's Architecture