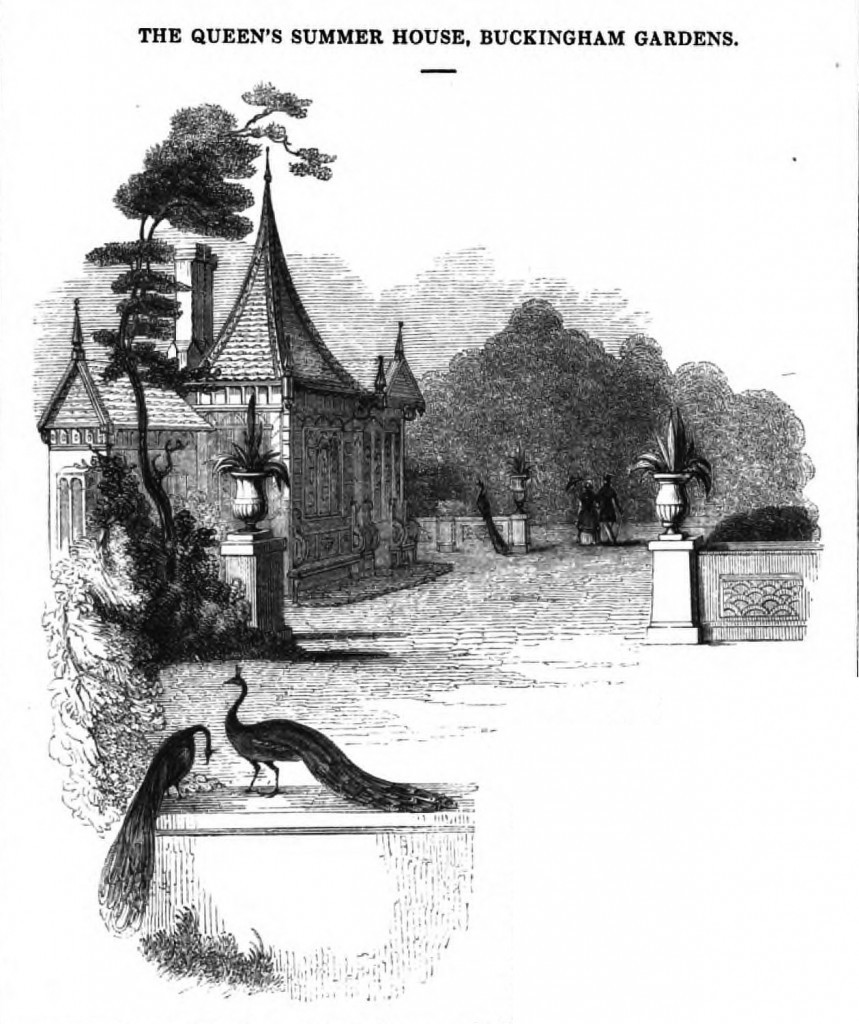

The Queen's Summer House, Buckingham Gardens

From The Art-Union 4 (1844): 37-38. Sourced from HathiTrust.

Our readers are aware that, not long ago, Prince Albert commissioned eight of the leading British artists to execute for him eight frescoes--as adornments to a small summer-house recently built in the garden attached to Buckingham Palace.

Although the experiment cannot be described as altogether satisfactory, due regard must be had to the disadvantages under which it has been made. Before we commence our description of the work, it is our duty to express very earnest gratitude to his Royal Highness, who has been the first patron in Great Britain to try it at all: other patrons have talked over the matter: it is to the honour of our most excellent Prince that he was not content with mere "wordy speculation"; but has at all events afforded to the artists of the country--though adopted, yet emphatically his own--opportunities of exercising their "'prentice han'" in the, to them, "New Art."

First let us describe the building which contains the frescoes. It is a small octagonal structure, which crowns the summit of an artificial hill, built without any design to be thus richly decorated; and, therefore, not calculated for the proper display of the treasures it contains. The light is obtained from a latticed door and four small latticed windows, and does not fall happily on the pictures. The style of architecture is in accordance with the architect's whim; at least it belongs to no order; this may be no very serious objection, considering that it was intended to be little more than a garden seat; but it is an evil, now that it is likely to become an object of universal interest and attraction. The one room of which it consists (we take no account of two small apartments behind, and the aviary, which forms an underground floor, falling with the hill) is, as we have said, octagonal--but an irregular octagon; two of the eight sides being much larger than the other six. From these eight sides run up to a point in the roof, sixteen compartments; each of these compartments being occupied with a design in arabesque by Mr. Aglio, which that gentleman has executed in encaustic. It would be the height of injustice to him if we did not at once admit the great merit of his designs and the manner in which they have been painted; but they do inconceivable mischief to the frescoes above which (and as if running from them) they are placed. The encaustic colours are very brilliant; the frescoes are, on the contrary, somewhat dull; so that the glaring hues of Mr. Aglio go far to kill the tones of Mr. Leslie and Mr. Maclise, while Mr. Aglio himself sustains much injury by their neighbourhood; for in his designs he has introduced several figures, semi-human--and has been placed at a manifest disadvantage in being seen in juxtaposition with the first artists of the age. This is an evil which time will not remedy; but as the interior of the building is quite unfinished, much may yet be done to give the frescoes "fair play"; not, we trust, by overloading subordinate parts with ornament, enriching up sides and skirtings, painting windows, and other gaudy additions of which Rumour speaks. Upon the "finishing" will mainly depend the ultimate effect of the "experiment."

The poem illustrated in "The Masque of Comus;" and the frescoes are (or rather are to be) in number EIGHT; the artists charged with their execution being Messrs. EASTLAKE, LESLIE, STANFIELD, MACLISE, ETTY, UWINS, E. LANDSEER, and Sir WILLIAM ROSS. Mr. Eastlake and Mr. Landseer have not commenced theirs;--the other six have completed their works; and of these we are enabled to judge and report. We shall notice them in the order in which they occur--according to the plan upon which they have illustrated the poem; commencing with that by Mr. Stanfield.

We must premise that the size is very limited--six of the eight being about five feet by two feet six inches; and the other two being, perhaps, each a foot longer. Consequently the figures average generally no more than ten or twelve inches in height. The shape is a semicircle; and in the spandrels of the arch are, or are to be, two small illustrative figures, executed by the producer of the fresco and in the same materials. These probably will not be above six inches by eight. It is understood--and there can be no impropriety in stating the fact--that the artists undertook the work without regard to pecuniary advantage; being--as they ought to have been--desirous of seconding the views of the Prince in this experiment; and that her Majesty and his Royal Highness have both manifested a strong personal interest in the result, and made almost a daily inspection of the work while in progress.

No. 1, then, is the fresco of Mr. STANFIELD. It is of the larger size, and placed above the door. The excellent and accomplished artist selected, as the point to illustrate, that passage from the prologue in which the attendant spirit, habited as Thyrsis,* watches the revels of Comus and his crew. The full moon is shining most brilliantly upon a fall of water rushing and foaming over huge stones, overhung with wild shrubs; a graceful tree rises from the centre of the picture; at the foot of it stands the shepherd with his dog, listening to the distant howls--

"Midnight shout and revelry,

Tipsy dance and jollity,"

and marking the onward progress of a hideous crowd (seen by an unnatural light), whose "human countenances" had been changed

"Into some brutish form of wolf or bear,

Or ounce, or tiger, hog, or bearded goat."

The work of Mr. Stanfield is very beautiful. The "new material" seems to have been perfectly familiar to him; there has been evidently no constraint, no timidity, no apprehension of danger; the difficulty has been fearlessly encountered and entirely overcome. The picture is to the full as excellent as if had been painted on canvas.

No. 2 is the production of Mr. UWINS. Less free in execution, more cautious, and--it is scarcely too much to say, embarrassed--it is still a very admirable work. "The lady is described" as passing among the perils of the enchanted wood, the foul enchanter hiding behind a tree; deformed monsters are lurking about; while she

"------------------------Attended

By a strong-sided champion, conscience,"

sings to call her brothers to her aid. The figure of the lady seems too thick and heavy, and that of Comus too tall. The fine feeling of the excellent artist is, however, apparent in the expression conveyed into the countenance of the lady--that "something holy" which the painter has caught from the poet and nature.

No. 3 is by Mr. LESLIE. It pictures the offering of the cup. The lady is seated, while the enchanter addresses her:--

"If I but wave this wand,

Your nerves are all bound up in alabaster,

And you a statue."

The "blithe son" of Bacchus and Circe is a capital reading of the character; and the skill of the artist is exhibited in the attendants--nymphs, a Puck, and satyrs--hardly concealed from the lady's sight, but peering from behind the pillars of the splendid chamber. The lady is a most exquisite creation; her wrath, as she exclaims--

"Hence with thy brew'd enchantments, foul deceiver."

is forcibly and most happily given. The execution of the work lacks the freedom we look for at a master-hand. There is, however, no poverty in the colouring, and the drawing is unobjectionable. Still there is, to our mind, evidence of constraint--such as we do not find in the oil-paintings of the artist. It is nevertheless by no means so apparent as to induce a fear that a difficulty exists which may not be overcome.

No. 4 is by Sir WILLIAM ROSS. He has chosen the moment when the brothers rush in, "with swords drawn," break the magic glass, and expel the enchanter and his crew. The attendant spirit enters; but the lady sits--

"In stony fetters, fix's and motionless."

It is a fine picture, very skillfully grouped, and executed with remarkable freedom. The face of the lady is truly a "Gem" of Art.

No. 5 is the compartment above the fireplace, left for Mr. EASTLAKE.

No. 6 is by Mr. MACLISE. We cannot overrate this most noble and beautiful work--a perfect triumph both in conception and execution; objectionable only on the ground that it is too full; that every part of it seems to have been studied with equal care; that there is no one immediately striking point to date from--as it were; the artist, having been over anxious, has, it may be, done too much. The painter has selected the moment when Sabrina, having been evoked by the attendant spirit, disenchants the lady. The brothers watch with intense anxiety as Sabrina, attended by her water nymphs, sprinkles on the lady's breast

"Drops that from my fountain pure,

I have kept of precious cure."

The attendant spirit standing on the right of the picture, anticipating the event in calm confidence, strikingly contrasts with the earnest expression of the brothers on the left. The surrounding figures are exquisitely grouped and arranged, and are the creations of a delicate and fertile imagination. But the glory of the picture is the Lady in the Enchanted Chair. The chair itself is a singularly novel invention--subordinate, but exhibiting rich fancy; the figure placed in it is wonderfully fine: one of the noblest productions of modern Art. All the accessories are good, well made out, and skillfully combined--a rich vein of poetry runs through the picture from such minor details as the broken glass in the foreground up to the great triumph--the Lady in the Chair. Mr. Maclise seems to have been little, if at all, embarrassed by the new material with which he worked. There is nearly as much freedom and ease in this fresco as in his oil-paintings.

No. 7 is the compartment left for Mr. Landseer.

No 8 is the work of Mr. ETTY. It pictures

"My mother Circe, with the Syrens three,

Amidst the flowery-kirtled Naiades;"

but is, in all respects, unsuccessful;--thin and meagre in colouring, inconceivably bad in drawing, and miserably poor in conception. How so entire a mistake has been made we are at a loss to imagine; but assuredly it may serve to carry conviction, that to paint in fresco can be by no means an easy task, when the attempt to work in it has been so signal a failure on the part of an artist anything but deficient in ability, knowledge, and experience, and who cannot but be perfectly conversant with all the frescoes of the best old masters.

We cannot at present devote greater space to this very interesting subject; it is probable we shall recur to it when the work is completed--the eight frescoes all finished, and the several "accessories" in their respective places. It is, just now, very difficult for any observer to form an accurate idea as to the effect of the whole, for, as we have intimated, the only portions that can be said to be completed are the arabesque decorations of Mr. Aglio; and of these, only such as run from the frescoes up the ceiling, but not to the point of it, for between these arabesques and the point, occurs a space of intense blue, by which the entire work is prejudiced. This, however, we understand, is to be subdued by the introduction of stars; whether this will diminish or increase the evil is, nevertheless, a question.

We cannot, however, close our remarks without expressing regret that these examples of fresco were not made on a larger scale--as decorations for some more important chamber. Still, it is something to have induced actual experiments from eight of our leading British artists; their "second attempts" will be, of course, infinitely more successful; and again we may be permitted to say, the country has incurred a new debt to his Royal Highness the Prince Albert, who has already done more for the "New Art" than all the noblemen of England put together.

* Mr. Stanfield has been somewhat premature in giving to the attendant spirit the shepherd’s garb, which he does not assume until long afterwards.