A Visit to the Garden Pavilion in the Grounds of Buckingham Palace

Chambers's Edinburgh Journal. Saturday, August 30, 1845

Amongst the subjects of public attention in London last month, was the newly-finished summer-house or pavilion erected by her majesty and Prince Albert in the grounds connected with Buckingham Palace. Tickets having been issued to enable a limited portion of the public to see this novel object, and one of these having fallen into the hands of a friend, I was enabled to pay the place a visit. For the information of those who are not familiarly acquainted with London, I may begin by mentioning that Buckingham Palace--built in the Reign of George IV.--occupies a somewhat disadvantageous situation on the west side of St James's Park, contiguous to the suburban district of Pimlico. In the rear of the palace is a piece of pleasure ground, comprising wood and lake, and really a beautiful retired scene, notwithstanding that the roar of Piccadilly speaks, in a way that cannot be mistaken, of the near neighbourhood of an active city. Between the grounds and the adjacent suburb, an artificial mound, covered with shrubbery, helps to shut in the place; and on the summit of this mound is perched a small Chinese-looking building with a little platform in front. This is the Pavilion.

The external appearance is by no means impressive. Many a lodge at a gentleman's gate is finer. It is on entering that we become aware that something extraordinary is intended. The fact is, that the queen and her consort have here made an experiment in that combination of Decorative Painting with Architecture, for which Italy is remarkable, but which has as yet been scarcely exemplified in our own country. The great and affluent in England have recently been made comparatively familiar with this style, by the publication of a superb work by Mr L. Gruner, embodying the decorations contributed by Raphael to the Vatican, and the similar productions of other Italian masters. When her majesty, therefore, determined on having this summer-house decorated in such a manner, she very appropriately employed Gruner to direct the general arrangements, and engage the various artists and others required for the purpose. So much being premised, let us step across the threshold, and inspect what it requires no great stretch of imagination to conceive as a fairy palace.

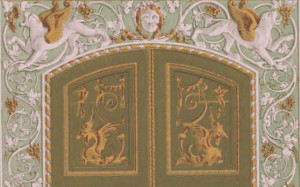

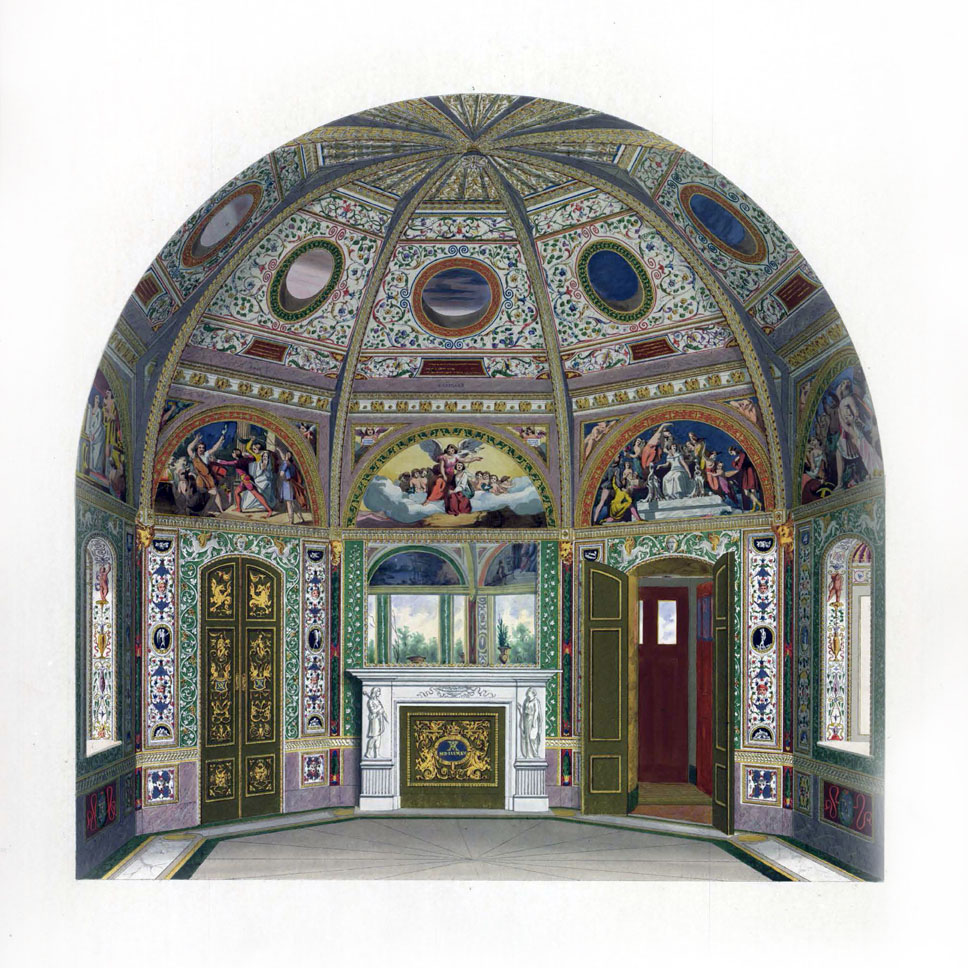

We enter at once a small octagonal room (15 feet 8 inches in diameter, and 15 feet in height), being, little as it is, the chief room of the building. From the gray marble floor to the centre of the vaulted ceiling, it is one blaze of the most gay and brilliant colouring. Before, however, going into the particulars of the decoration, let us see the remainder of the house, in order to have a general idea of its character and proposed uses. Opposite, then, to the entrance of this room are two doors, occupying compartments in the octagonal arrangement, but having one compartment containing a fireplace and mirror between: these lead into two smaller rooms (8 feet 10 inches by 9 feet 7 inches, and 12 feet in height), betwixt which is interposed a small kitchen, provided with every suitable convenience. Such are the whole accommodations.

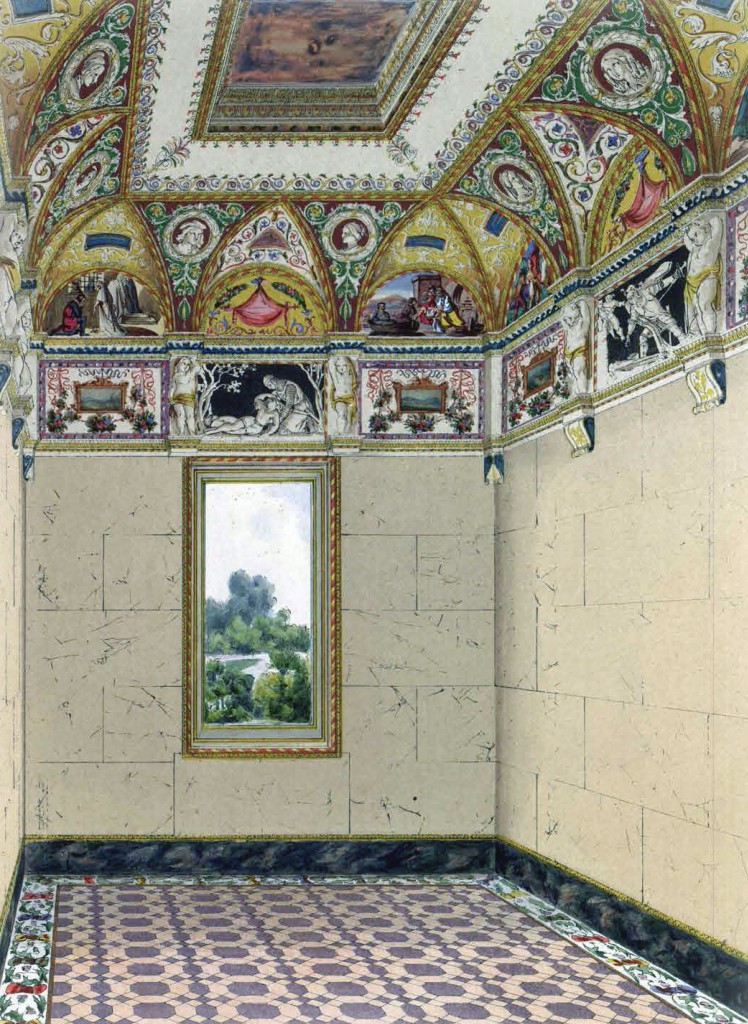

View of the Sir Walter Scott Room from Gruner, Decorations, p. 24

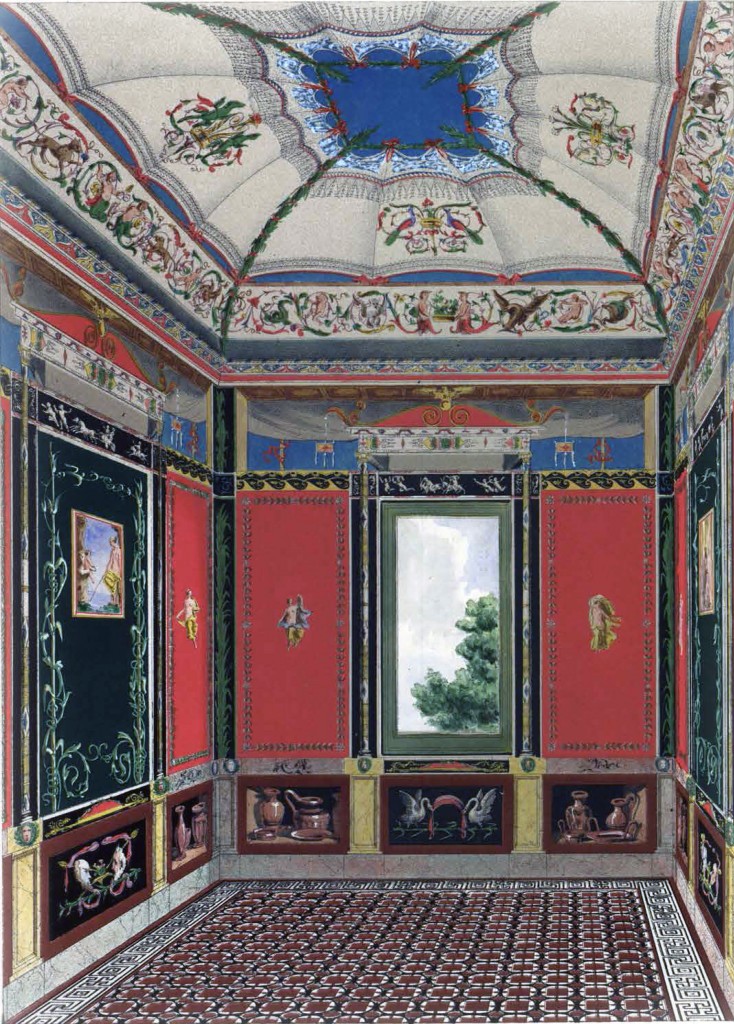

View of the Pompeii Room, from Gruner, Decorations, p. 23

The principal or octagon room is an illustration of Milton's youthful production, the Masque of Comus, 'in itself, like an exquisite many-sided gem, presenting within a small compass the most faultless proportion and the richest variety.'* The suitableness of this poem for being illustrated in such a room, where more heroic and solemn subjects would have been altogether inappropriate, must strike every one. "Comus,' says Mrs Jameson, 'at once classical, romantic, and pastoral, with all its charming associations of grouping, sentiment, and scenery, was just the thing fitted to inspire English artists, to elevate their fancy to the height of their argument, to render their task at once a light and a proud one; while nothing could be more beautifully adapted to the shades of a trim garden devoted to the recreation of our Sovereign Lady, than the chaste, polished, yet picturesque elegance of the poem, considered as a creation of art.'

From the eight angles of the room rise as many 'ribs,' which, meeting in the centre, form a dome-shaped roof, divided into eight compartments. In these are painted circular openings, with a sky background, for the purpose of indicating the time of the scenes depicted below: those on the west side present midnight, with its star, and those on the east the approaching dawn. At the point where the walls and dome meet, there is a rich cornice, below which are eight lunettes or semicircular spaces, filling the upper portion of the eight sides of the room; and in these lunettes are as many frescoes, or paintings upon plaster, containing scenes from the poem. Each lunette is six feet by three, and over each is a tablet, on which is inscribed in gilt letters, on a brownish-red ground, the particular passage of the poem which has suggested the subject of the picture. All of these paintings are by English artists of the highest reputation. Such are the chief objects which meet the eye in this room: there is, besides, a great quantity of minute ornament. The spandrils, or angular spaces left by the curves of the lunettes, are occupied by figures relating to the subjects of the respective pictures. Beneath the lunettes are panels adorned with arabesques, in harmony with the main subjects.

Over each door are winged panthers, in stucco, with a head of Comus, ivy-crowned, between them. Beneath each window is the cipher of her majesty and Prince Albert, encircled with flowers.

The pilasters running up the angles of the room present, in medallions, figures and groups from a variety of Milton's poems--as Eve relating her dream to Adam, Adam consoling Eve, 'the bright morning star, day's harbinger,' Samson Agonistes, &c. Red, blue, and white mingle beautifully in this profusion of ornament, by which the eye is for some time too much dazzled to apprehend the details.

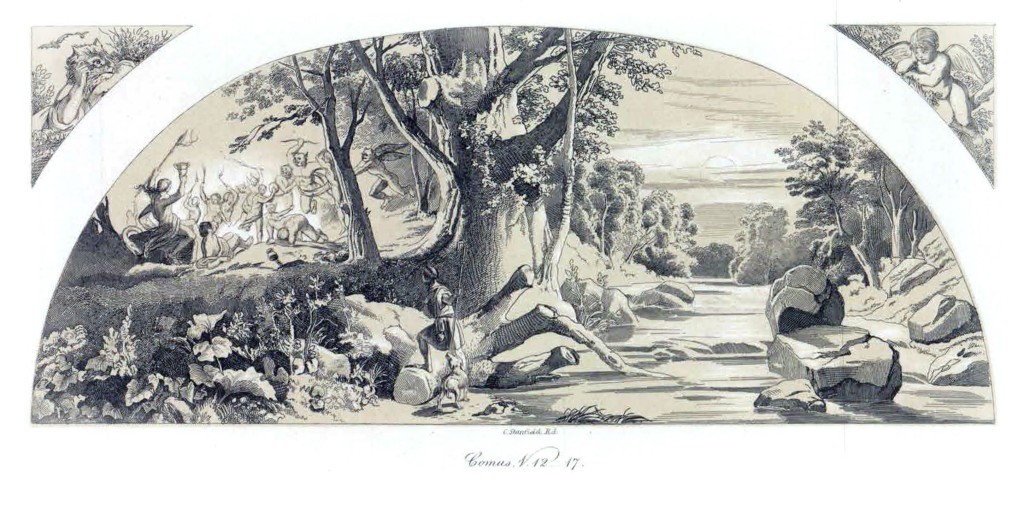

The Masque of Comus was a compliment paid by Milton to the Earl of Bridgewater, then residing in Ludlow Castle as president or viceroy of Wales. It was acted at Ludlow before the earl's family in 1634. The story is of the simplest kind, relating only how a lady lost her way in a wood, and, falling under the enchantment of Comus, a son of Bacchus and Circe, was with some difficulty rescued and restored to her friends. Besides Comus and the lady, the characters presented are her two brothers, an attendant spirit who puts on the guise of a shepherd, and Sabrina, the goddess of the Severn river. In the age following that in which Spenser spun his fine allegories, and Drayton personified every wood and stream in the country, this union of ancient mythology with British scenery, and the calling in of a river spirit for the protection of a benighted young lady, would appear sufficiently rational. The first lunette (by Mr. Stanfield) is designed to realize the passage near the commencement of the poem, in which the attendant spirit speaks of his errand being to those exceptions from the common run of human beings who

by due steps aspire

To lay their just hands on the golden key

That opes the palace of eternity.

The scene is a landscape--a river flowing through forest scenery; the spirit, in shepherd weeds, is seen leaning meditatively upon his crook, while in the background, through the glade, we see the rabble rout of Comus holding their nocturnal orgies by torchlight. In the spandrils are a cherub weeping and a fiend exulting. In the poem, the spirit describes Comus's birth and character, and his haunting 'this tract that fronts the falling sun,' for the purpose of tempting weary travellers to drink of his glass, when,

Soon as the potion works, their human countenance,

The express resemblance of the gods, is changed

Into some brutish form of wolf or bear,

Or ounce or tiger, hog, or bearded goat,

All other parts remaining as they were;

And they, so perfect in their misery,

Not once perceive their foul disfigurement,

But boast themselves more comely than before.

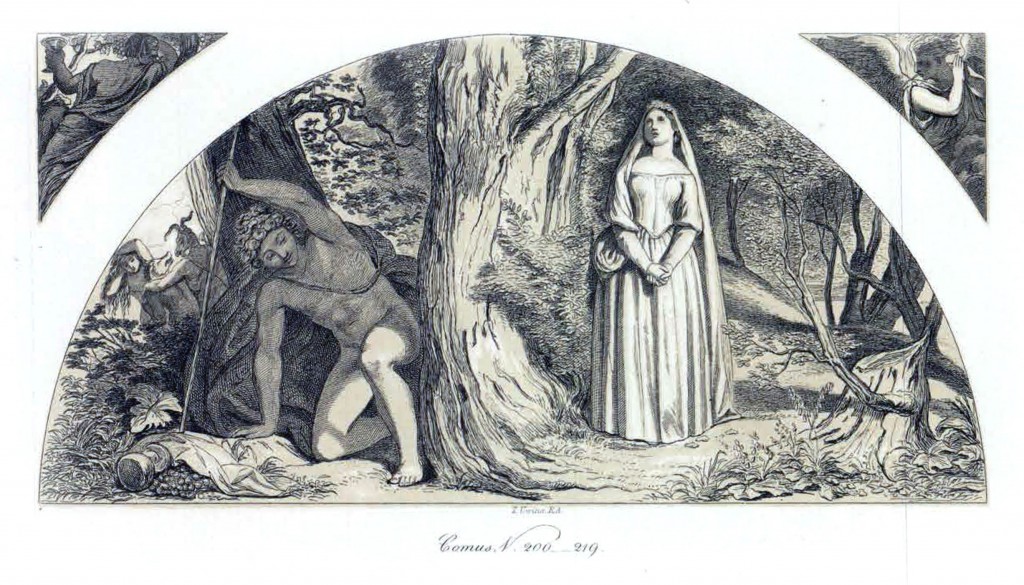

The spirit announces his own function to be the preservation of 'any favoured of high Jove' from the spells of this dangerous deity. Comus then enters, and proposes to commence his usual revels for the night; but presently an interruption takes place, from the entrance of the lady, who, having been left for a while by her brothers, had wandered on through the forest till thick night overtook her, and she had become exhausted with fatigue. The second lunette (by Mr. Uwins) represents her standing under an oak, saying,

This is the place, as well as I may guess,

Whence even now the tumult of rude mirth

Was rife, and perfect in my listening ear;

Yet nought but single darkness do I find.

What might this be? A thousand fantasies

Begin to throng into my memory,

Of calling shapes and beckoning shadows dire,

And airy tongues that syllable men's names

On sands, and shores, and desert wildernesses. * *

Was I deceived, or did a sable cloud

Turn out her silver lining to the night? * *

Comus is seen amidst the neighbouring foliage listening to her soliloquy. In the spandrils, a seraph looks down with anguish, and a satyr with triumph.

Comus appearing before the lady as an honest homely swain, the lady agrees to accept his hospitality; and when they have left the stage, the two brothers enter, to express their distress at the loss of their sister. Some parts of their conversation betoken, in the Milton of six-and-twenty, what he was to become in his riper days.

Wisdom's self

Oft seeks to sweet retired solitude,

Where with her best nurse contemplation

She plumes her feathers, and lets grow her wings,

That in the various bustle of resort

Were all too ruffled, and sometimes impaired.

He that has light within his own clear breast,

May sit i' the centre, and enjoy bright day:

But he that hides a dark soul, and foul thoughts,

Benighted walks under the mid-day sun;

Himself in his own dungeon. * *So dear to Heaven is saintly chastity,

That when a soul is found sincerely so,

A thousand liveried angles lackey her,

Driving far off each thing of sin and guilt,

And in clear dream, and solemn vision.

Tell her of things that no gross ear can hear,

Till oft converse with heavenly habitants

Begin to cast a beam on th' outward shape,

The unpolluted temple of the mind,

And turns it by degrees to the soul's essence,

Till all be made immortal.

The attendant spirit, in his shepherd dress, joins them with intelligence of their sister, of whom the three then proceed in quest.

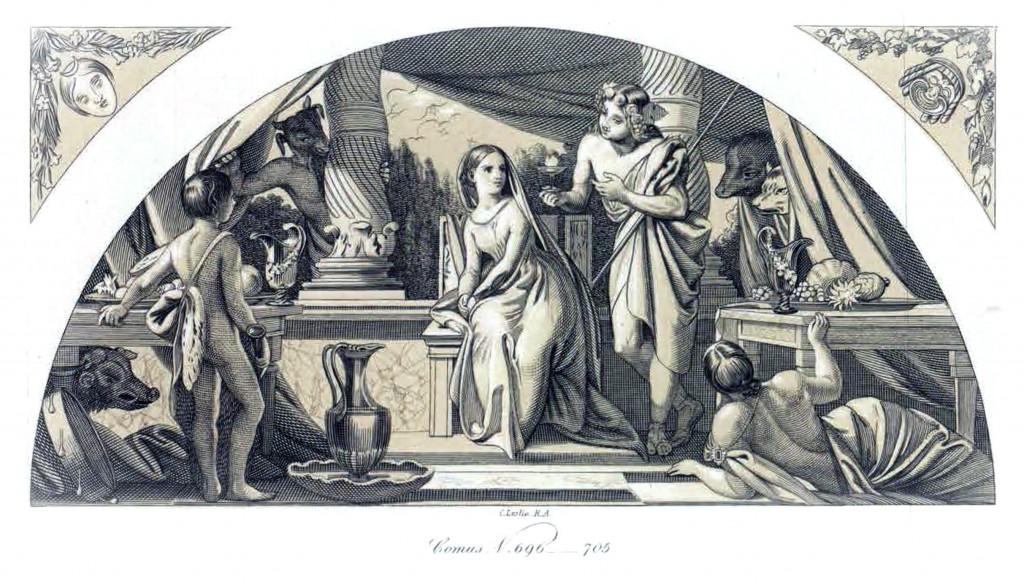

The next scene presents the lady sitting in a palace, 'full of all manner of deliciousness,' while Comus tempts her, the brutish rabble standing by. This is the subject of the third fresco (by Mr. C. Leslie), the precise point being that when the lady exclaims,

Hence with thy brewed enchantments, foul deceiver!

Hast thou betrayed my credulous innocence

With visored falsehood and base forgery?

Were it a draft for Juno when she banquets,

I would not taste thy treasonous offer.

After a colloquy between the two, in which Comus confesses himself foiled by her words, the brothers rush in with drawn swords, wrest his glass out of his hand, and break it against the ground: his rout make sign of resistance, but are all driven off. The attendant spirit then enters, and says,

What! have you let the false enchanter 'scape?

Oh, ye mistook; ye should have snatched his wand

And bound him fast.

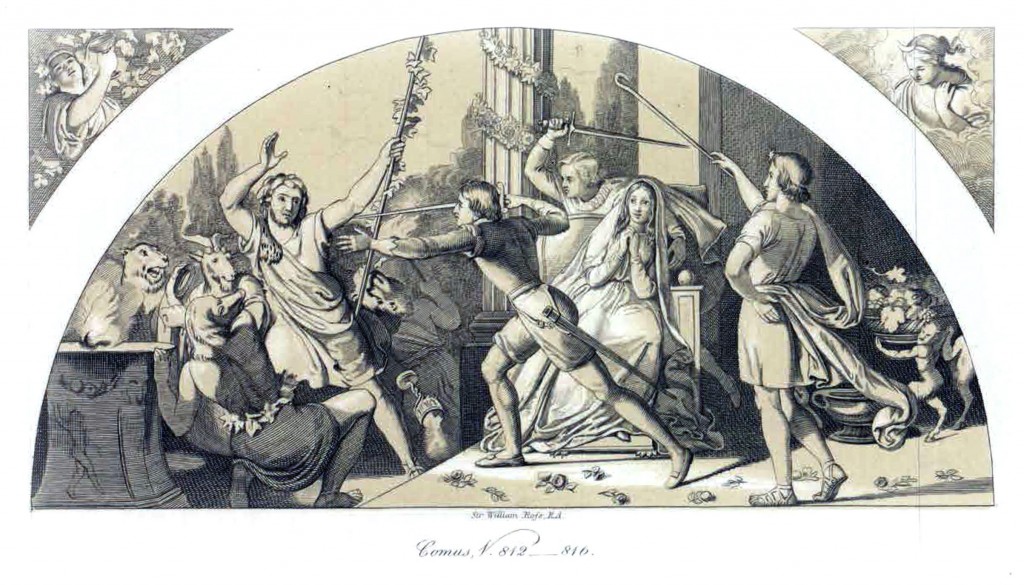

This incident is the subject of two of the lunettes; an unlucky consequence of the artists having been left to choose the subjects from the poem at their own discretion. Fortunately, however, they present the subject in styles so dissimilar, that no one at first sight could detect the identity. In Sir William Ross's picture, the lady in her chair forms the central figure, while the enchanter is seen flying off at the side from before an armed figure.

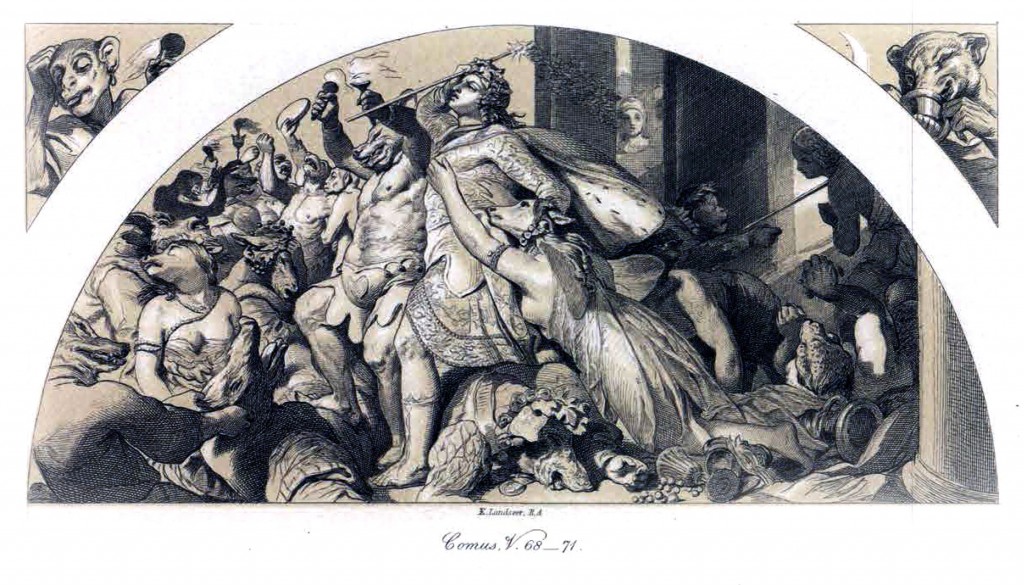

In Mr Landseer's painting, we have Comus's rabble presented most conspicuously, their animal heads affording a most appropriate subject for the peculiar genius of that artist.

Comus, alarmed at the appearance of the armed brothers, receives a Baccchante with a greyhound's head, who has thrown herself upon his arm. The mixture of grotesque and imaginative in this picture, and the union of tipsy stupidity and terror in the separate figures, render it by far the most remarkable picture in the series, though it certainly is far from being the most pleasing.

To return to the poem: the lady being fixed by enchantment to her chair, it is necessary to call in the aid of the river goddess, Sabrina, who, having been duly invoked, rises from her cave, and says

Brightest lady, look on me;

Thus I sprinkle on thy breast

Drops that from my fountain pure

I have kept of precious cure.

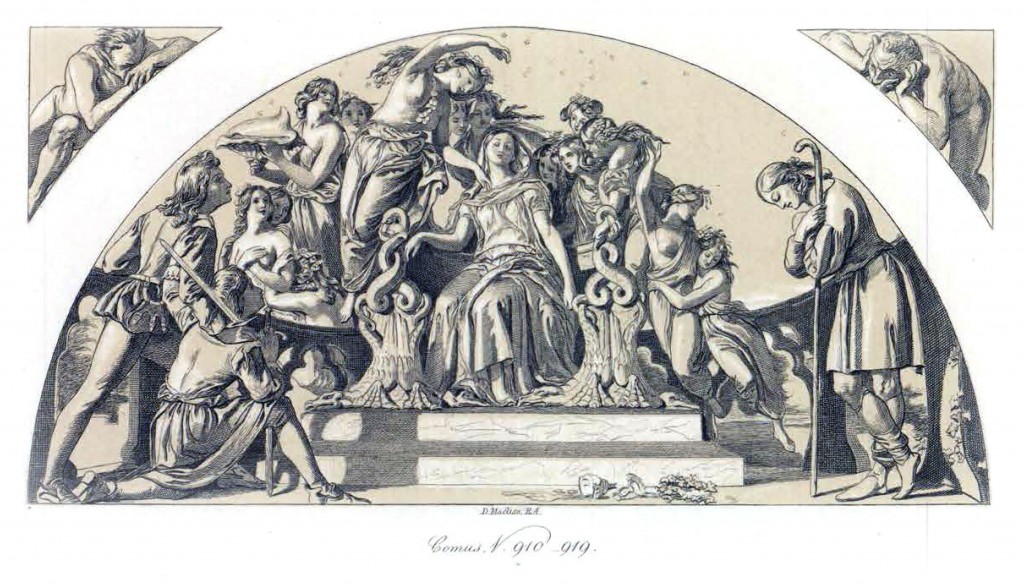

This is the subject of Mr Maclise's fresco, which is marked by his usual liveliness and brilliancy, profusion of figures, and painstaking in their execution. The lady sits in her chair 'in stony fetters fixed and motionless.' Sabrina and her attendant spirits hover around her. One nymph presents in a shell the water of precious cure, which Sabrina is about to sprinkle over the victim of enchantment. The brothers and the star-browed spirit stand by. In the spandrils are two of the rabble rout looking down in affright.

The lady, being now disenchanted, returns with her friendly guardians to her father's mansion, where she and her brothers are presented to their parents by the spirit.

Noble lord and lady bright,

I have brought ye new delight;

There behold, so goodly grown,

Three fair branches of your own;

Heaven hath timely tried their youth,

Their faith, their patience, and their truth.

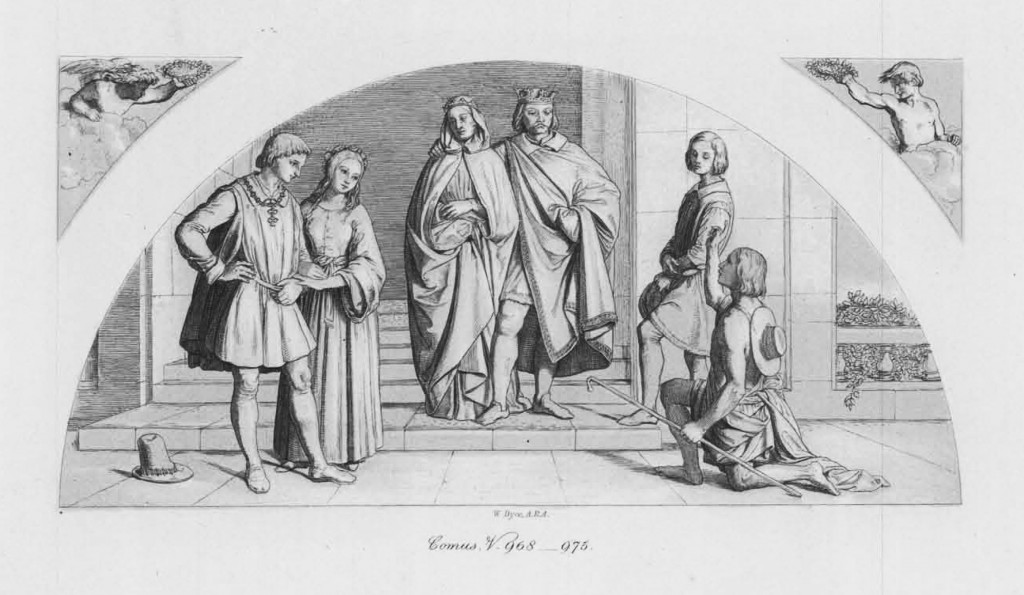

Mr Dyce gives us this scene in a very pleasing picture, 'graceful, simple, full of intelligence, and the colouring rich without trickery,' according to a critical contemporary. In the connecting spandrils are two guardian angels presenting crowns of white roses and myrtle. In conclusion, the spirit flies to

Happy climes, that lie

Where day never shuts an eye,

but first calling on mortals to follow virtue. She, he says,

can teach you how to climb

Higher than the sphery chime;

Or if Virtue feeble were,

Heaven itself would stoop to her.

The two last lines, with which the poem terminates, are the subject of the last fresco of the series (by Mr. Eastlake), where Virtue is represented fainting upon the high and rugged path, and succoured there by a seraph; while Vice, represented by a serpent, is seen gliding away; a choir of angels leaning from the clouds above, to receive the coming visitant.

Having thus at some length given a description of the chief room, I proceed to the next, which may be called the Scott Room, since its decorations wholly bear reference to the productions of that illustrious person. The four sides of this apartment are painted in imitation of gray veined marble, so exquisitely, that I only became aware of their not being real marble after I returned home. Round the upper portion of the walls runs a rich frieze, presenting three compartments on each side, the central one a bas-relief in white stucco on a blue ground, the side ones paintings of small size, representing views of places celebrated by Scott.

Here we have Melrose, Abbotsford, Loch Etive, Dryburgh Abbey, Craig Nethan, Loch Awe, Aros Castle, and Windermere Lake, painted by Mr E. W. Dallas from Mr Gruner's sketches. In the bas-reliefs we have groups from the poems--Clara recognizing Wilton on the field of battle, Bruce raising his page from amidst the slain (these two by Mr Timbrell), William of Deloraine taking the book from the magician's tomb, and Roderick Dhu overcome by the Knight of Snowdown (these last by Mr J. Bell). In eight lunettes are as many scenes from the Waverley novels,

the production of different artists, two of whom are, I understand, sons of the celebrated caricaturist (Doyle), who usually passes by the name of H. B. Eight heads in white stucco, surrounded by arabesques in relief, represent as many of Scott's heroines. This completes the list of figures, but not the whole ornaments of the room, for the flooring--not yet laid down--is chequered, and surrounded by a border of thistles, along with festoons of the various tartans of the Highland clans. Only one specimen of the tiles forming this pavement was shown when we visited the pavilion; it contained the tartan of the Camerons, with the name of that clan inscribed upon it. In 1745, this kind of cloth was looked upon at court as a spell to raise fiends: in 1845, it is cherished in the most private domestic retreats of royalty as a memorial of a romantic period of our national history. In a late visit to Hampton Court, I observed a picture equally indicative of change of times and of feelings; namely, a portrait of the poor old Chevalier taking his place among the other royal personages who figure in such profusion in that palace.

the production of different artists, two of whom are, I understand, sons of the celebrated caricaturist (Doyle), who usually passes by the name of H. B. Eight heads in white stucco, surrounded by arabesques in relief, represent as many of Scott's heroines. This completes the list of figures, but not the whole ornaments of the room, for the flooring--not yet laid down--is chequered, and surrounded by a border of thistles, along with festoons of the various tartans of the Highland clans. Only one specimen of the tiles forming this pavement was shown when we visited the pavilion; it contained the tartan of the Camerons, with the name of that clan inscribed upon it. In 1745, this kind of cloth was looked upon at court as a spell to raise fiends: in 1845, it is cherished in the most private domestic retreats of royalty as a memorial of a romantic period of our national history. In a late visit to Hampton Court, I observed a picture equally indicative of change of times and of feelings; namely, a portrait of the poor old Chevalier taking his place among the other royal personages who figure in such profusion in that palace.

The remaining small room is designed as an imitation of the style which prevails in the ancient city of Pompeii; all the ornaments, friezes, and panels being suggested by, or accurately copied from, existing remains, except the coved ceiling, which is the invention of Mr Augustine Aglio. 'This room,' says Mrs Jameson, 'may be considered as a very perfect and genuine example of classical domestic decoration, such as we find in the buildings of Pompeii--a style totally distinct from that of the baths of Titus, which suggested to Raphael and his school the rich arabesque ornaments in painting and relief which prevailed in the sixteenth century, and which have been chiefly followed in the other two rooms.'

I spend fully two hours in perusing the pavilion in all its various parts, and yet left it without having got above half way through its bewildering minutiæ. The work as a whole, and in its parts, has been keenly criticised by those who assume the duty of warning the public against being too much pleased with books, pictures, and other productions of the finer intellect of our species. It had, doubtless, some faults and infelicities, the want of harmony being, I think, the chief. Yet, taken as the first English attempt at such a style of decoration, and considering the merely nascent condition of art in our country, I cannot help regarding the whole as creditable, and calculated to afford pleasure to the exalted personages for whole use the little mansion is designed.

* Mrs Jameson's introduction to a volume entitled 'The Decorations of the Garden Pavilion of Buckingham Palace, engraved under the superintendence of L. Gruner.' 1845.